Love it or hate it, there’s no denying that Steven Spielberg’s latest movie Ready Player One– based on the novel by Ernest Cline – was a commercial hit. In an age where the real-L.I.F.E immersive qualities of Virtual Reality are only beginning to be explored, Cline’s story of a digital Willy-Wonka-style Golden Ticket hunt clearly spoke to modern audiences.

Of course, Webcomics long pipped Parzival at the top of the leaderboard, having used their digital platform to explore life within simulations for almost as long as the medium has existed. Today, we’re looking at one of the clearest examples, and dissecting how it’s built its own Oasis for readers to escape to.

Not a Villainby Aneeka Richins

“Not a Villain” has been exploring the ways people live and play in virtual worlds since 2010, under the all;e hand of writer and artist Aneeka Richins. The comic follows the exploits of Kleya and her game group as they work towards securing a place as players of The Game, the monetised branch of the world-encompassing virtual reality L.i.F.e. For some players, the Game is a welcome distraction from their post-apocalyptic world and the drudgery of working in the fields to produce food for the survivors. For others, the money from the Game and the privilege to access L.i.F.e is literally a matter of life and death…

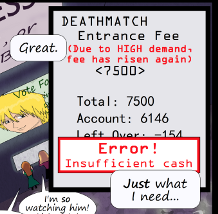

L.i.F.e is an interesting virtual world to compare against the commercial juggernaut of Cline’s Oasis. In a lot of respects, L.i.F.e represents the kind of virtual reality that could have existed had Parzival failed and the evil corporation IOI had seized control of the game. In L.i.F.e, almost everything is pay-to-play, and micro-transactions abound. Don’t want to look poor? You’ll need to pay to upgrade your skin. Don’t want your account to be a potential target to hackers? You can rent an apartment to log out from, or leave your avatar in one of the free ‘napping’ areas while you’re not using it. And if you log out without getting to one of those free areas, you can expect a fine. Similarly, trials for the Game are pay-to-enter, and if you’re knocked out or voted out for not being popular (and therefore commercially viable) enough, you get to start at the beginning – too bad if you had bills to pay, or kids to feed…

TENka, like IOI hoped to do, rule over the virtual world with impunity. They are the gatekeepers of the game, the rule-makers, the attendants and the providers – and they profit from that. They control the majority of the real world’s stable resources and due to their influence, keeping L.i.F.e updated is a higher global priority than rescuing people stranded outside cities (who can’t pay for the Game), repairing real-world city infrastructure, medical care or global environmental reparations. Similar to IOI, TENka also uses their access to technology to cheat in the game. They are (nominally) the only ones who can employ hackers to change the game’s code in their favour, and although you can access L.i.F.e from any system that can run it, you can only play the Game if you own TENka’s proprietary immersion rig – the Kido. Through that rig, and their access to the code, they have absolute power to track, watch and remove any player from the Game if they feel that player is not earning them enough profit, ejecting that player back into cold reality. And if they’d had their way before the ending, that technology would have migrated into their player’s very central nervous systems, with potentially dire results…

In L.i.F.e, as in the Oasis, people log in to escape the visceral horror of their reality. In the virtual world, you can be who you want, look like you want, socialise with your friends and live in a place that feels secure and safe. Whereas the world outside the Oasis was crumbling, with nuclear attacks on major cities, resource shortages, terrorism and fantastical urban density, the world outside L.i.F.e is even more dire. Here, society hascrumbled – thanks to the worldwide devastation of ‘the ending’ and the wide scale destruction of infrastructure by global war and the rampant ecological disaster of the earth’s magnetic field destabilising. The division of people’s physical bodies across Cline’s and Aneeka’s work therefore impacts the way their players interact with the online world. Oasis users log in to reclaim something of the world they had before their civilisation’s decline – a world where travel, shopping, entertainment and sport were all readily available and easy to access. For them, the fantastical elements of the Oasis – planet hopping, spacecraft, magic and sci-fi technology – add flavourto the reality they’re experiencing. And that reality – the online world – has become the place where they spend most of their time, earn their money, and truly live: which is one of the themes behind Cline’s cautionary tale.

The reality supporting L.i.F.e, however, is more brutal, with basic commodities such as food, water and even atmospherebeing difficult to come by outside of the safe zones. As such, access to the virtual world is more for the very act of ensuring survival, than it is an ‘escape’ from reality. If you’re stranded in a small group or alone, the money you can pull from the Game or various jobs in L.i.F.e (like Mina’s singing career) – which can then pay for food or medical deliveries – is the key to your survival. There are no other options, and if that means you stay logged in so long you accidentally starve to death working towards that paycheque, well… that happens.

So, if you liked Cline/Spielberg’s Ready Player One, or if you were interested in seeing the themes of living virtual lives explored without the rampant nostalgia-bait of that world, then Not a Villainmight just be the webcomic for you – after all, this is just the settingfor the amazing story Richins weaves within it, and trust me when I say that setting is exploited very well to tell her story.

What do you think about the exploration of virtual realities through these two properties? Do you see more similarities or differences we haven’t highlighted here? Don’t hesitate to let us know in the comments below or on Twitter, and until next time, remember: don’t eat the clickbait!