So Hellboy, Brooklyn, Frasier and DEATH walked into a bar…

Ok, but you got to admit they’re kinda close! In fact, although Boredman’s take on the book and characters of Revelation (as reviewed by Steve and Jason in Episode 497 of the podcast) is as unique as it is brilliant, Christian theology has long been a source of material for a wide range of media like television, movies, novels and, of course – webcomics.

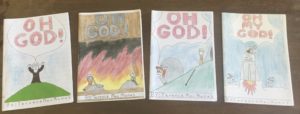

Or even what passed for cartooning in the days (circa 2003) before this author had heard of ‘webcomics’…

Today, we’ll be looking at how Apocalyptic Horseplay weaves the minutia of Catholic Dogma around the apocalypse into its narrative, and how the distinct personalities of characters like Mot, Warrace, Pesty and Marvin reflect the historical interpretations of their generally more sinister selves.

Apocalyptic Horseplay is a comic that, appropriately, rides on the strength of it’s core characters: Mot, Warrace, Marvin and Pesty – the most recent incarnations of Death, War, Famine and Pestilence. But these characters have had a wide range of interpretations over the years, and besides War and Death the roster of the four horsemen of the apocalypse has been far from stable (ha! Horse joke!) over the past millennia. Across all interpretations, the riders could consist of Death (atop a pale – or green – horse), War (as either the red or the white rider), Famine, Pestilence, Conquest, Prosperity, Oppression, Destruction, the Antichrist or even Christ himself. Boredman notes that he decided on the four most common interpretations of the horsemen for his comic and, whilst that’s broadly true it must be noted that ‘conquest’ has strong historical precedent over ‘pestilence,’ with the latter only coming into real popularity during the 20th Century. Indeed, the passage from Revelations which describes this rider states:

“I Looked, and behold, a white horse, and he who sat on it had a bow; and a crown was given to him, and he went out conquering and to conquer” –Revelation 6:2.

In one of the comic’s Q&As, Boredman defends his use of ‘pestilence’ over ‘conquest’ partly for artistic reasons (after all, ‘Conquest’ is pretty similar to ‘War’) and partly due to his own interpretation of elements such as the association of archery – and therefore the bow carried by the white horse rider – with disease (indeed, many depictions of the plague in medieval iconography show the plague hitting victims as crossbow bolts) and the inarguable colonisation analogue of disease upon a host. Certainly the character of Pesty makes it work, with his zealous care for all things bacterial and his delightfully pustulant design endearing him to the reader in a way a conquistador might have found difficult (and the use of his sight by the Vatical Council’s Order of St. Sebastian makes for a key narrative hook).

The other riders of Boredman’s apocalypse much more closely reflect the common interpretations of their purpose – Warrace’s powers to incite violence and his declaration in the comic is consistent with interpretations of War’s abilities:

“to take peace from the earth, and that men would slay one another” –Revelation 6:4.

Similarly, the characterisation of Marvin – a nickname derived from ‘Famine,’ bears much of the iconography associated with the black horse rider. Although we only see the rider’s weapon of choice – a set of scales – used once in the comic (and to devastating effect), the way Marvin operates is rather reflective of his character. Hardly found without a cigarette hanging from his jaw, this character is historically associated with society’s excesses and the inequality between the wealthy and the poor. Not for nothing is he the only rider who speaks in Revelations, saying:

“A quart of wheat for a denarius, and three quarts of barley for a denarius; but do not damage the oil and the wine” –Revelation 6:6.

Or, in other words, “drive up the prices of basic commodities, but leave the luxury goods unaffected for the rich.”

In similar style, Marvin in the comic rankles under the leadership of Mot and is the only horseman to regularly go out into the world and use his powers. He likes his position of power and privilege over the rank-and-file humans, meting his own form of justice to – mainly the common folk. In turn, he appears to come perilously close to driving a family-owned pub out of business, fulfilling his role as harbinger of inequality.

Finally, at the end, there is Death.

Mot, Death, Thanatos… whatever he’s called, death is by far the most depicted and well-known of the horsemen, and an appropriate leader for the motley crew of the story. He is the only horseman named by the prophet James in Revelation, and unlike the other horsemen is not said to be carrying anything with him – although many interpretations depict the Death rider with a scythe, that iconography truly belongs to the unrelated character of ‘the Grim Reaper;’ a psychopomp (remember those?) who began to be depicted with the scythe in European folklore following the Black Death and it’s near literal harvest of souls.

Boredman, clearly, has done his homework, and is careful to also never depict the horseman carrying this scythe. Instead, the scenes we see of Mot ‘in action’ clearly show another means of harvest… one that might feed into the very leading description given to us by Revelations:

“I looked, and behold, an ashen horse, and he who sat on it had the name Death; and Hades was following with him.” –Revelation 6:8.

The association of the Death rider with Hades – Hell and Satan – is also explored within the comic. Death is the only character to have interacted with Lucifer, and it’s strongly suggested he had been in regular contact with the Prince of Lies before the horsemen’s retirement. Mot seems to be shouldering the greatest burden for his past actions out of all the horsemen, and it’s no surprise to consider that as a result of his leadership across the centuries, pushing the horsemen towards the apocalypse at the behest of Satan.

But even within this tale of the apocalypse, there are some loose ends. We know from Revelations that the four horsemen are loosed onto the world through the actions of an individual – “the lamb” – breaking the first four seals of the book of revelation, but we still haven’t heard if this character exists in Boredman’s story, nor if they were responsible for releasing the horsemen or if they simply coalesced out of the elemental forces they represent. Similarly, the appearance of the antichrist in the tale opens up an entirely new avenue of Christian dogma – but that, dear readers, is an article for another time.

What did you think of Apocalyptic Horseplay? Did you enjoy the way Boredman has developed the characters of the horsemen, or would you rather have seen them approached differently? Are you new to, or familiar with the aspects of Christian dogma presented through depictions of the Vatican, holy relics and the exorcists of the series? Can you ever think of pestilence again without reading him with Kelsey Grammar’s voice? Let us know in the comments below or on Twitter, and until next time always remember: don’t eat the clickbait!